BODY WORK IS POSSIBLY BLACK MAGIc

Welcome to Yoga Class, my name is Severus and I’ll be your instructor today.

You might have had this experience before. You’re in yoga class, or acupuncture, or massage, or whatever, and you’ve got this pain. Let’s say it’s a pain in your knee. And you’re complaining about this pain in your knee and this person you’re with - this ‘body worker’ as they call them - just… just completely ignores your knee. Instead they do something weird to your shoulder, or your toes or the back of your neck. And just as you’re about to object and be like, “um… do you even know where my knee is?” your knee stops hurting.

Now you’re freaked out. This is black magic. How did that little adjustment to my shoulder fix my knee? What is this person doing? Are they a wizard? Is this a dream? We’re confused because, as far as we could tell, the problem was in the knee. Therefore, the solution should be in the knee. Right?

Right…?

OUR BRILLIANT, STUPID BRAINS

Here’s something weird but true; the way most of us learn to see bodies is wrong. Not exactly wrong as in the information is incorrect, but in the way that it’s incomplete. When we learn about bodies we are, mostly for efficiency purposes, taught a highly mechanical idea. In this idea the body is separated into “parts” that operate independently. They cooperate, to be sure, but their functions are isolated.

This way of thinking is helpful, it simplifies things. When we take the body apart into little bits we make it easier to comprehend. So we learn piece by piece how the body works. However, if we get stuck in this way of thinking, we lose the (literal) big picture. The forest is much more than just a collection of trees.

Think about a bicep muscle. Pretty standard, run of the mill muscle. Not too complex, it pretty much does one thing; bend your arm at the elbow. Fine, no problem there. But if we only see the bicep this way we will miss an entire field of activity involved in bending the arm.

How will I ever complete today’s essential errands with my all consuming nose-itch problem?

Let’s say you are standing in a checkout aisle and you get an itch on your nose. When you lift your forearm to scratch it, your center of gravity moves. Maybe not a lot, but it definitely moves. Your body has to account for this shift in weight; your shoulder and neck tense up just so, your torso makes millions of micro-adjustments to hold you stable, and your legs distribute this little shift all the way down through your feet and into the ground. Energy has to transfer throughout the system instantly, without thought, to adjust for a movement in your arm. Your bicep might seem to be the only thing in action but in reality you never just move an arm, you move your whole body.

Basically, there’s no such thing as a “bicep.” Not really. ‘Bicep’ is just a concept, a term we use to describe a particularly dense bundle of a particular type of cell. It’s an illusion, but a necessary one.

YOU NEED TO BE WRONG MOST OF THE TIME

I know it’s delicious, but why is it delicious?

Our brains didn’t evolve to understand everything, they evolved to keep us alive. Our minds are finite, puny things that are constantly doing their level best to keep us going. There is absolutely no evolutionary need for us to have all the information, we just run on life’s Cliff’s Notes. If you’re gathering food, you’re not going to spend mental energy on understanding the molecular composition of a tangerine. You simply figure out the best way to get a hold of that orange orb in a tree and keep surviving.

The idea that your body is a composite of isolated pieces is a necessary illusion, we simplified the body to make it halfway accessible to our limited minds; a hand is a hand, a tooth is a tooth, a spleen is a spleen, etc… We need this illusion, it is absolutely fundamental to our basic function in the world. If we didn’t divide the thing up into rudimentary chunks we’d have no way to understand and discuss our bodies. So celebrate! Your amazing mind pulls an amazing trick! It’s helping! Well done, mind. Have some toast.

NOW WE ARE STUCK

But wait! This illusion is great because it helps us function in the world. It’s not so great when we confuse it with, you know, reality.

Oh god no my arm…

Let’s say that same bicep of yours gets torn during a wild polo match in Argentina. Under the false assumption (illusion) that your bicep is some kind of isolated bit of your body, you put a cast on your arm. This cast will keep your arm bent and stable until the muscle heals. It’ll take about six weeks, let’s say.

Sadly, over the course of that six weeks the the muscles in your forearm atrophy from lack of use, the tendons in your elbow freeze up and shorten, your shoulder develops strange tension patterns from holding the arm in one position for so long, which makes your neck tweaky and your back starts to spasm, and oh-my-God pretty soon you’re never going to play polo again.

See, you treated just one ‘part’ of the body and lost sight of the interconnected nature of the system. It’s not your fault, it’s just our default way of thinking. Doctors did this kind of thing with casts and braces and immobilization for a long time. (Luckily, the trial and error was helpful. Doctors and PTs don’t do this much anymore.) These days, smart people try to get you moving again as soon as it’s safe, because movement is full-body integration.

If we get “stuck” in the illusion that your bicep is just one, isolated part of you, we make bad decisions on how to heal. The illusion was helpful - necessary, even - for learning the basic concepts about your body, but it’s not the whole story. The whole story is something much more complex and interconnected.

THE WHOLE STORY (NOT THE WHOLE STORY)

…EVER SINCE CREATION, ALL BEINGS ATTAIN IGNORANCE BY THE DELUSION BORN OF DUALITY, O ARJUNA.

Bhagavad Gita, 7:27

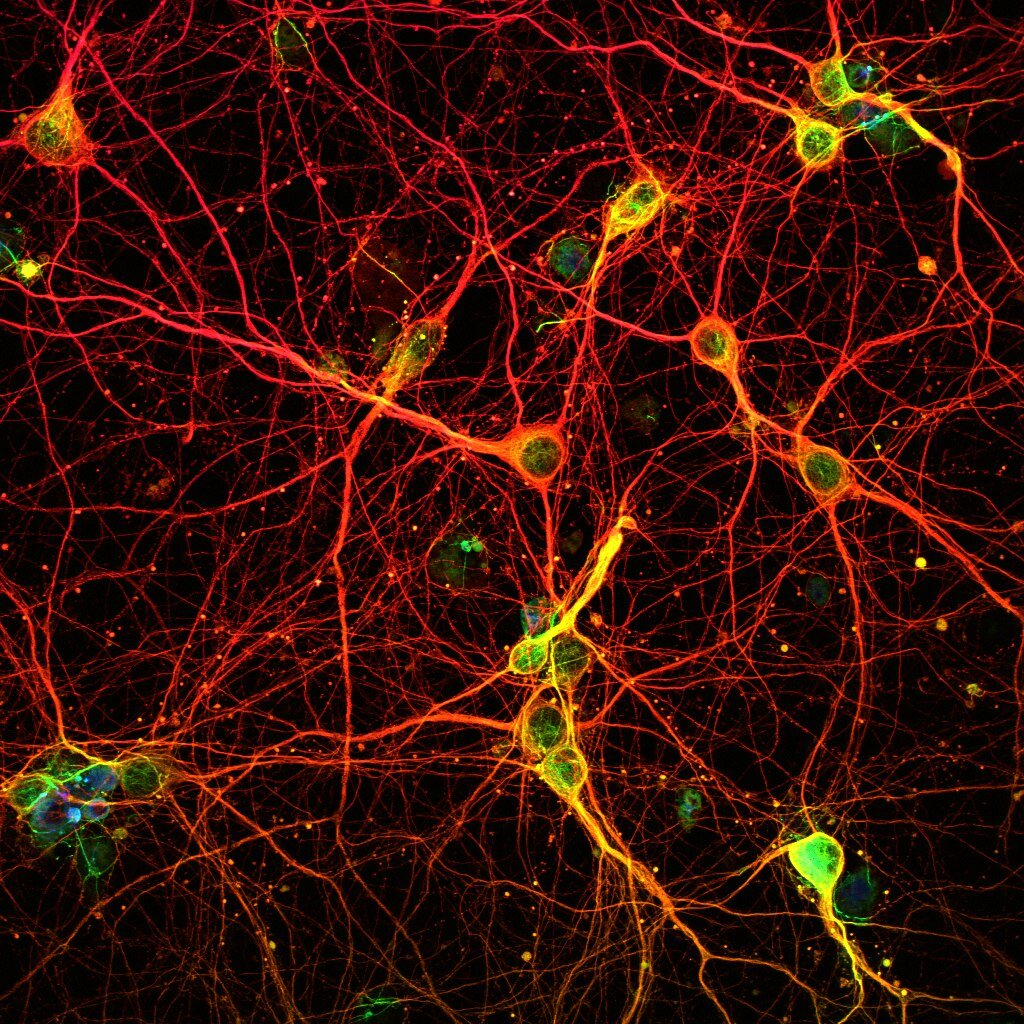

Your every movement contains trillions of micro-actions and reactions. You’ll never catch them all. You’ll never understand them all. But you can appreciate their existence. Your body is doing ridiculously complex things at all times, and a lot of it has nothing to do with your brain or even your nervous system. It’s doing them without you knowing or thinking about them. You’re just… happening. It’s amazing! It’s terrifying. (Who is running this ship, anyway…?)

Even a ‘Holistic’ image of the body is incomplete. We’re using a new illusion to talk about the old one. (We could go around for hours.) The point is you’re not an assembly of parts. That’s the necessary illusion. You need to see yourself in parts to get by from day to day, but the truth is something different entirely.

OH MY GOD KYLE WHAT IS THE POINT

I mean, look, it’d be great to have everyone feel a deep connection with their physical bodies as undifferentiated holistic entities. I’d dig that. But this is really about much more than that. When we practice Yoga we discover that our bodies are microcosms; if we listen closely they can teach us about the world around us, and perhaps even the nature of reality itself. Physical insight can illuminate fundamental, powerful truths.

So here’s one:

We all create necessary illusions to make life manageable for our simple minds.

This is where the rubber meets the road in yoga practice, where brain science and Hinduism really groove together, where philosophy of the mind and ancient spirituality intermingle. It’s where humility sneaks in. It’s where new-age woo-woo actually has some ground to stand on. Because listen, if we construct necessary illusions about our bodies where else do we make them? Where else do we draw arbitrary lines?

You don’t have to look to hard to find them. Race, class, nationality, citizenship, gender, generations, political parties, and even time itself are all organized along arbitrary boundaries. These are the illusions we conjure to make the world make sense. Even things we think are “hard” lines, like the idea of distinct animal species or the boundaries of physical matter start to break down the harder you look at them.

It’s… it’s weird. And the point isn’t to try and resolve the weirdness. We’re not here to be right. We will never be totally right in the literal, logical sense, we don’t have the cognitive power. Human beings aren’t made to comprehend their existence on an intellectual level, we’re just too small. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try, though. In many ways the work - the practice - is to acknowledge and embrace our limitations, and then continue to act in the world. Get really close, or really far. Change your perspective, figure out where you’re wrong, challenge your mind to solve the puzzle and see what it comes up with. Dive into the mystery and try to find its bottom.

(Spoiler Alert: You won’t.)

all the way down